Looking beyond COVID-19, about the future of our health

E-magazine

A publication of the Public Health Foresight Study (PHFS) | Dutch edition published on 27 November 2020

Foreword

RIVM (Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu) has been publishing Public Health Foresight Studies for 25 years. However, this extra edition of the Public Health Foresight Study (PHFS) is different, because 2020 is a very different year. Taking COVID-19 into account, this document takes a closer look at future trends in public health. As a result, the PHFS edition presented here may be different than usual, but it is powerfully relevant.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound effect on our daily lives. Besides the direct consequences for health, the COVID crisis has entailed so much more. The economic and societal impact has been immense, and the full extent is not yet known. People have lost their jobs, their income and their freedom of movement. We keep our distance from others, work from home, see each other less often, and even when we do, it is often on a 2D screen rather than in 3D and in person.

Even if we limit our frame of reference to the impact on public health, the consequences extend far beyond morbidity and mortality due to COVID-19. What are the health challenges we face in the Netherlands as we are confronted with this new virus, now and in the future? This corona-inclusive PHFS (c-PHFS) provides an important contribution to answering to this question. This study also looks at the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 on the demand for care and on the health-relevant living environment. The latter concept includes busy cities and the presence of green spaces within the urban context.

The most important challenges in public health, health care and the living environment do not change as a result of the COVID crisis, and have therefore also been mentioned in the earlier editions of the Public Health Foresight Study. However, COVID-19 causes some challenges to grow even more significant or urgent. For example, the COVID crisis has a particularly profound impact on vulnerable groups in the Netherlands, which is why the crisis can exacerbate existing health inequalities.

Future trends in health are accompanied by major uncertainties, and these uncertainties have certainly not diminished. We do not know how COVID-19 will progress from here. We also do not know what the exact consequences will be for health and society. What we do know is that COVID-19 has a huge impact on our health and what we can and cannot do, and that impact is not limited to the immediate present or the near future. And what we also know is that there are different visions of what a desirable future looks like. We see that reflected in the approach to the COVID crisis. This broad foresight study contributes to a better understanding of potential and desirable futures. As a result, this edition of the Public Health Foresight Study makes a valuable contribution to a sound, wide-ranging consideration of possible policies. Many RIVM staff and colleagues from outside our institute have worked hard on this publication, in times when it was already very busy. That makes me even prouder that we have managed to make this extra edition of the Public Health Foresight Study together. I hope that you, the reader, can benefit from it and make good use of it, and that it contributes to knowledge to support policy.

Hans Brug

Director-General of RIVM

Reading guide

This e-magazine offers an overview of the key findings from the corona-inclusive PHFS. The e-magazine is intended to present these findings to a broader audience in a compact and accessible way. The key messages are clustered into four themes: COVID-19, health, health care and living environment. These four themes describe how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected many topics, and may potentially have a future impact in these areas as well. The e-magazine also addresses what these developments mean for the future challenges that our society faces. The overarching key messages are intended to provide input and direction on how to broaden considerations in the future.

Content

Major uncertainty; that much is certain

Any research that seeks to explore the future is accompanied by uncertainties, and this foresight study is no exception. The uncertainty we face in the COVID-19 crisis seems to be different in nature, however. How will the course of the virus develop over time? When will a vaccine be available? What changes in human behaviour can be observed? Is there still widespread support for the measures that were put in place to control the pandemic? Many uncertainties are already becoming apparent in the short term, but the health impacts may only be fully revealed in the long term.

The Public Health Foresight Study explores future possibilities to establish a clearer understanding of these uncertainties and their possible effects. Knowledge about the pandemic and its consequences is growing rapidly, but is still far from comprehensive. The constant availability of new knowledge, and how to incorporate the latest insights into the foresight study: it is a diabolical dilemma. Moreover, new knowledge does not always reduce uncertainty.

Despite the uncertainties, this foresight study provides a number of recurring themes and indicators that can facilitate progress in policy and in society.

Key messages

Key messages

The novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) holds the whole world in its grasp. The consequences have been huge, in the Netherlands as well as elsewhere. Mortality from COVID-19 will probably be in the top 3 causes of death in 2020. Average life expectancy has been shortened by six months in 2020 compared to earlier projections. It should be noted that the excess mortality from COVID-19 in 2020 does not have an impact on life expectancy in the long term.

The virus does not only directly affect morbidity and mortality. As the health care system shifted focus to address the crisis at hand, non-urgent care was put on hold, leading to scaled-down access to regular health care. Our lifestyle changed and our social activities have been limited by the coronavirus measures. Partly as a result, mental health is also under pressure: many people feel anxious, despondent and lonely more often. These effects may be amplified during the future course of the pandemic, as consequences of an economic setback also become visible. Various population groups will be hit particularly hard.

It is difficult to say what the COVID crisis means for the future of public health. We do not know how the number of infections will progress from here. We also do not know yet exactly when there will be a vaccine, and how effective it will be. However, the expectation is that the virus will be present and occupying our minds for some time yet. What we also know is that we do not all have the same vision of what a desirable future looks like in terms of public health. Considering multiple perspectives helps us not to forget that diversity.

Health challenges in society becoming even more urgent

The Public Health Foresight Study 2018 identified three major challenges to public health in the Netherlands: 1) the persistently high burden of disease due to cardiovascular disease and cancer; 2) the growing group of older people still living on their own while suffering from dementia and other complex issues; and 3) the increasing mental pressure on teenagers and young adults.

These challenges have become even more urgent due to the pandemic. The virus and the measures intensify pressure on mental health. This applies to almost everyone, and to teenagers and young adults in particular. As a result of the COVID crisis, smokers are smoking more on average and the number of overweight people is continuing to rise. Those are significant risk factors for cancer and cardiovascular disease. Since these diseases are increasingly survivable, more and more people are dealing with the long-term effects of having had them. These survivors could potentially have a more serious course of illness from COVID-19.

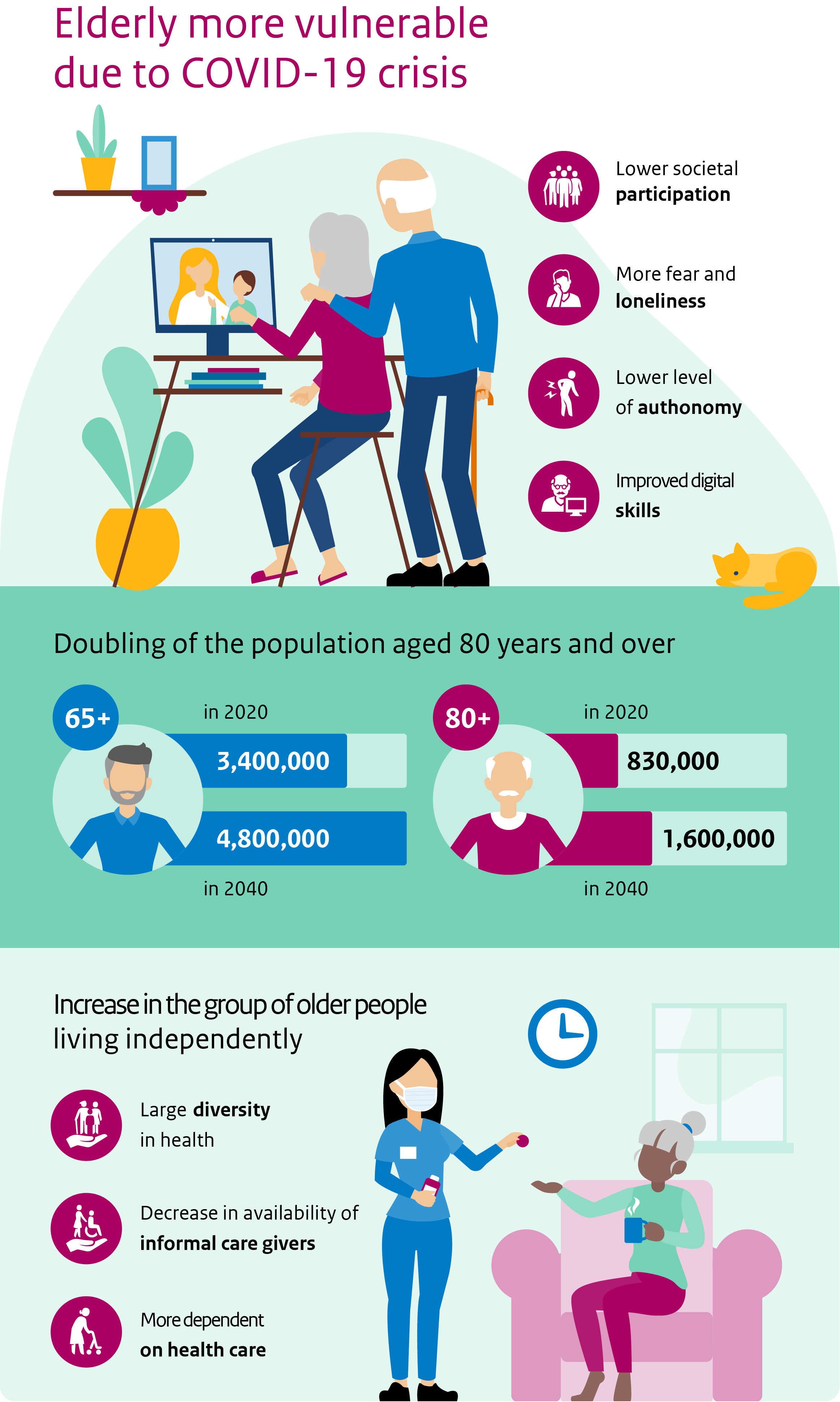

Older people are living independently for longer and are increasingly confronted with dementia and other complex health problems. COVID-19 poses additional health risks to these people in particular. Moreover, the COVID crisis makes it more difficult to organise proper care and support for them. This may increase their sense of loneliness.

Dividing lines between population groups are sharpening

There are clear and persistent health inequalities between population groups in the Netherlands. These inequalities occur along different dividing lines, such as education and income, living environment, migrant background, age and gender. The pandemic has caused the existing divisions to become even sharper. The crisis seems to hit harder among people who are lower educated. They contract the virus more often and are more likely to have risk factors that worsen the course of illness if they do get COVID-19. They are also more likely to have uncertain jobs that are the first to vanish in the event of an economic downturn. The combination of trends in this area are cause for concern, especially if the pandemic continues for some time.

The generation gap has also widened as a result of the COVID crisis. Young people feel that their freedoms are being restricted by the coronavirus measures, which are primarily intended to protect the older generations. The dividing line between generations is reinforced by the fact that ‘the elderly’ are all seen as vulnerable. This blots out the massive diversity in health and self-reliance among older people. The sharper dividing lines between age groups and stages of life can put further pressure on intergenerational solidarity.

Crisis as a turning point

In previous centuries, infectious diseases were the main medical challenge. Over the course of the 20th century, thanks to modern sewers and vaccines, attention shifted to diseases of affluence such as cardiovascular disease and cancer. The COVID crisis marks the start of a new phase, in which new infectious diseases will mingle with existing health problems. That means that we need to rediscover a new way of learning to live with the presence and threat of viruses.

Yet there is also hope that this crisis can be a turning point – to make our society more sustainable, healthier and greener, among other things. Various developments have been accelerated as a result of COVID-19. Examples include remote care and support, working from home, and the digital emancipation of older people who are have started video calling with their children and grandchildren. Awareness of the importance of good, accessible care and appreciation for health care personnel has also increased significantly. Also, the internal connections within districts and neighbourhoods have been strengthened, and people are perceiving a greater sense of calm.

The challenge is to overcome the COVID-19 pandemic, while at the same time retaining and reinforcing the positive developments that the crisis also brought about. There needs to be a focus on structural changes in behaviour in such areas as lifestyle, mobility and working environments. Smart use of the extra COVID-19 investments can contribute to this.

From analysis to action

From analysis to action

This foresight study identifies a number of future challenges to public health. Our analysis offers opportunities for parties at every scale, from local to global, to address the challenges expeditiously and to be better prepared for the future. The following four opportunities for policy and society have been identified.

1. Commitment to integrated prevention

The coronavirus measures in the social and physical living environment have an enormous impact on lifestyle. Smokers are smoking more, we are getting less exercise, and we have put on weight. The crisis confirms that lifestyle is more than an individual choice. Encouraging a healthy lifestyle requires integrated prevention that not only targets individual lifestyle factors, but addresses the social and physical living environment as well. Underlying social issues, such as debts and stress, often need to be resolved first, before creating room to work on a healthy lifestyle.

2. A future that includes chronic as well as infectious diseases

In every edition of the Public Health Foresight Study, the ageing population takes centre stage. It is possible to state fairly precisely how many people with dementia, diabetes or cancer there will be in 2040. This allows policy-makers to respond in a timely manner. Infectious diseases are much less predictable. If a pandemic suddenly emerges, it has an immense impact on health and on health care. In the coming years, this will require a balancing act in policy: sufficient focus on ‘plannable’ trends, as well as room to accommodate the unexpected. In addition, the convergence of chronic and infectious diseases requires new, integrated knowledge, new care concepts between formal and informal care, and more cooperation between different parties in health care and beyond.

3. Stronger focus on mental health

The increasing mental pressure on teenagers and young adults has become an even greater challenge as a result of the COVID crisis. Other age groups are also feeling more anxious, stressed, despondent and lonely. The expected economic downturn, which will hit certain population groups even harder, puts even more pressure on mental health. Better information and knowledge about our mental health is essential here, as well as offering future prospects to the people that are affected.

4. Urgency of continued cooperation between government ministries

The COVID crisis has led to intensified cooperation between the ministries. This interministerial cooperation also offers opportunities for further improvements in public health in the longer term. After all, many of the aspects that could be leveraged for this purpose lie outside the field of health, such as work and labour, education, the physical living environment and social security. In short: the urgent importance of working together towards better public health in the Netherlands, across the ministries, is underlined by the COVID crisis.

COVID-19 foto

COVID-19 Inleiding

COVID-19

COVID-19 is caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. How much do we already know about this novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) and the clinical presentation of COVID-19? How will the spread of the virus in the Netherlands go from here? Much is still uncertain. The future trends are described based on three scenarios. There is a possibility that SARS-CoV-2 or some other coronavirus will continue to cause outbreaks in the future, even if there is a vaccine against it. The Dutch population is ageing, the number of people with chronic conditions is increasing, and more and more people are overweight. As a result, the population becomes a little more vulnerable every year.

COVID-19 tekst

High burden of disease from first wave of COVID-19

The burden of disease from COVID-19 during the first wave is estimated at 58,500 Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs). In an average influenza season, the estimated burden of disease is 12,000 DALYs on average. That means that the burden of disease from COVID-19 is nearly five times higher than an average influenza season. The vast majority of DALYs due to COVID-19 (99%) are related to the years of life lost due to premature death. In the first wave, 6,142 people died who had a confirmed COVID-19 infection.

Minor fluctuations in R number, with major consequences

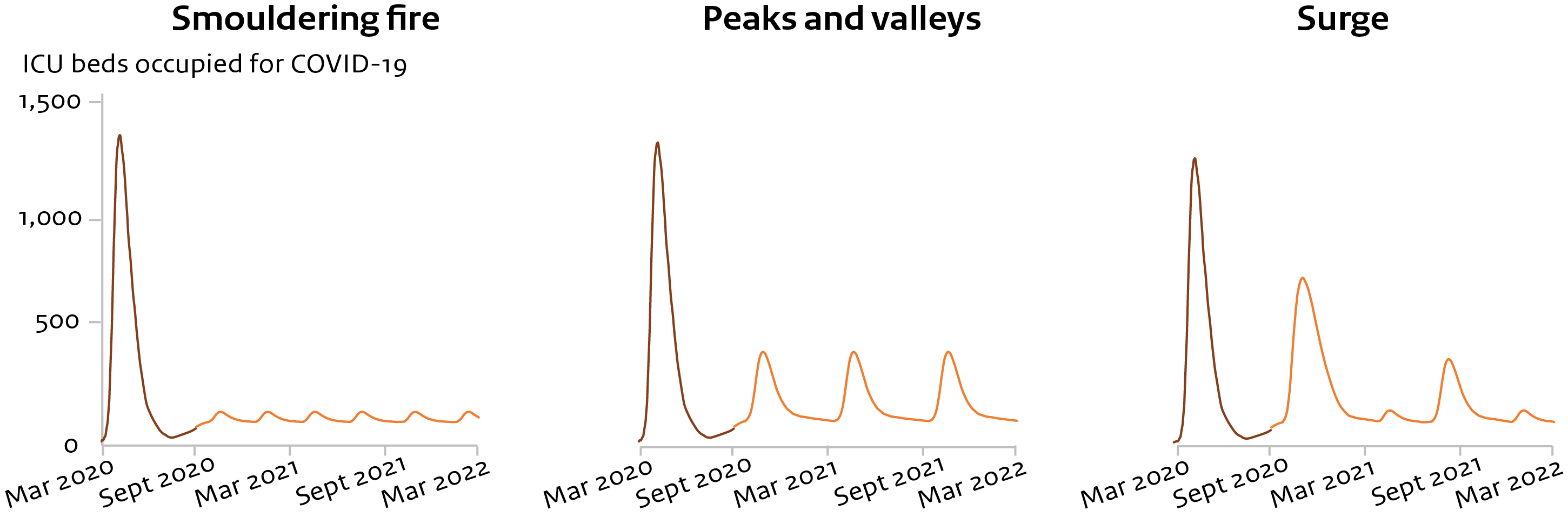

The future course of the COVID-19 pandemic is uncertain. For that reason, three scenarios are used to provide future foresight. These scenarios show that minor differences in the spread of SARS-CoV-2 can have major consequences for the number of admissions to intensive care units (ICU). Three scenarios have been developed that present the possible future trends for a potential future course of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Vulnerability of the population increases

There is a possibility that SARS-CoV-2 or some other coronavirus will continue to cause outbreaks in the future, even if there is a vaccine against it. The Dutch population is ageing, and the number of people with chronic conditions is increasing. Moreover, more and more people are overweight. As a result, the population becomes a little more vulnerable every year to developing a serious course of illness after infection with SARS-CoV-2, or a new virus that is comparable.

COVID-19 infographic

The COVID-19 theme consists of the following articles

The burden of disease from COVID-19 during the first wave is estimated at 58,500 Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs). In an average influenza season, the estimated burden of disease is 12,000 DALYs on average. That means that the burden of disease from COVID-19 is nearly five times higher than an average influenza season. The vast majority of DALYs due to COVID-19 (99%) are related to the years of life lost due to premature death. In the first wave, 6,142 people died who had a confirmed COVID-19 infection. The burden of disease increases to 87,900 DALYs if deaths and illnesses are counted for people who may also have had COVID-19 but were not tested. The long-term consequences of COVID-19 for the people who were infected are not yet known and have therefore not been included in the calculation. This means that the burden of disease from the first wave could still increase

COVID-19 burden of disease high, mainly due to premature mortality

The burden of disease from laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases during the first wave (until 1 July 2020) is estimated at 58,500 Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) (see table). The DALY is a measure of health loss, and consists of two components. Years spent living in reduced health (Years Lost due to Disability, YLD) and years lost due to premature death (Years of Life Lost, YLL). YLDs are calculated for mild cases, patients who are admitted to hospital, and patients in intensive care (ICU). Only the acute disease phase of COVID-19 has been included in the YLDs. The long-term effects of COVID-19 on people who were infected are not included in the estimated YLD. In the current estimate, 99% of the burden of disease from COVID-19 is caused by the YLLs.

COVID-19 burden of disease from first wave much higher than influenza

The DALY makes it possible to compare the burden of disease from different diseases. The influenza virus – generally the infectious disease that causes the highest burden of disease in the Netherlands – led to an average of 12,000 DALYs per season over the past five winters. The outlier was the 2017/2018 season, which reached 18,600 DALYs. This means that the estimated burden of disease from COVID-19 during the first wave was almost five times that of an average influenza season. In addition, it is more than three times higher than the worst influenza season in the past five years. The burden of disease from COVID-19 has been mitigated by measures to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Without these measures, the burden of disease would have been significantly higher.

COVID-19 burden of disease could potentially rise significantly

In reality, the burden of disease due to COVID-19 during the first wave was higher than 58,500 DALYs, since not all patients with symptoms resembling COVID-19 were tested for the SARS-CoV-2 virus in that period. For example, analyses of excess mortality show that approximately 9,900 more people died between March and July 2020 than usual during this period. If this excess mortality is attributed entirely to COVID-19, the number of DALYs increases to 87,600. The number of DALYs rises to 87,900 if we assume that there are 10 mild cases of COVID-19 per registered COVID-19 infection, and that the number of COVID-19 patients in hospital is underestimated by 10%. The burden of disease from COVID-19 obviously also increases if the morbidity and mortality from the second wave are also included.

Long-term effects of COVID-19 still unknown

The long-term consequences of COVID-19 for a person who was infected are still largely unknown. A possible consequence of COVID-19 could be the emergence of new patient groups with long-term symptoms. COVID-19 patients who were put on mechanical ventilation in intensive care may continue to have physical, cognitive and mental health problems. These are collectively referred to as post-intensive care syndrome (PICS). People who had a mild form of COVID-19 may also continue to have symptoms such as fatigue, headaches and heart palpitations for a long time. Depending on the duration and severity of these symptoms, the actual burden of disease from COVID-19 may increase further. It is also very possible that COVID-19 will influence the course and disease burden of chronic diseases.

Estimated burden of disease from laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases in the Netherlands during the first wave (until 1 July 2020). DALYs above 250 are rounded to tens, while DALYs higher than 2500 are rounded to hundreds

| Outcome | Number | YLD | YLL | DALY’s |

| Deaths | 6,142 | 9 | 58,300 | 58,300 |

| ICU admission | 2,903 | 114 | 114 | |

| Hospital admission | 11,573 | 50 | 50 | |

| Mild cases (not admitted to hospital | 34,648 | 48 | 48 | |

| Total | 220 | 58.300 | 58,500 |

ICU: Intensive Care Units, YLD: Years Lived in Disability, YLL: Years of Life Lost, DALYs: Disability-Adjusted Life Years

Want to read more?

The website presents more in-depth information on this topic (in Dutch).

The future course of the COVID-19 pandemic is uncertain. For that reason, three scenarios are used to provide future foresight. These scenarios show that minor differences in the spread of SARS-CoV-2 can have major consequences for the number of admissions to intensive care units (ICU). One of the scenarios is the ‘surge’ scenario with a reproduction number (R) of 1.8, in which measures are needed to contain the outbreak. The maximum occupancy of ICU beds by COVID-19 patients has been estimated at 800 here. In a scenario with short-term regional spikes, the estimated number of occupied ICU beds due to COVID-19 is limited to a maximum of 150. The number of patients in the ICU depends on such factors as the moment when measures are implemented and whether those measures are sufficient. The scenarios present possible future trends, and certainly not all possible visions of the future.

Much uncertainty about spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the future

The extent to which SARS-CoV-2 will continue to spread in the Netherlands over the next year is not yet known. Multiple factors will influence the course of events here. One important factor is which measures will be implemented to limit the spread of the virus, and how effective they are. This depends in part on the extent to which people comply with the measures. In addition, it is still unknown whether the virus can spread more easily in winter. It is also not yet certain to what extent and for how long a previous infection will offer protection against the virus. Finally, it is uncertain how effective a vaccine will be. All these factors make it difficult to estimate the reproduction number (R) – the average number of people infected by someone who has COVID-19.

Three COVID-19 scenarios for possible future course of viral spread

In view of the uncertainty, three scenarios have been developed for the future course of COVID-19. The scenarios present possible future trends, and certainly not all possible visions of the future. The scenarios are: smouldering fire (small spikes), peaks and valleys, and surge (see Figure 1). These scenarios do not yet include the effect of a vaccine. The scenarios have been developed using a mathematical model. The outcome measure is the number of ICU admissions. This is a limiting factor for health care capacity, and a reliable outcome to monitor the course of the epidemic.

Scenarios differ in the assumed R numbers

Table 1 outlines the three future scenarios and the corresponding assumptions. The aim here is not to describe the current second wave, but to show potential effects of different R numbers. The higher the R number, the faster the outbreak is increasing. The maximum reproduction numbers for the three scenarios are: increase to R=1.3 in the ‘smouldering fire’ scenario, increase to R=1.5 in the ‘peaks and valleys’ scenario, and increase to R=1.8 in the ‘surge’ scenario. The scenarios assume that more than 10 ICU admissions per day will be followed by measures, which will bring the R number back below 1. An R number lower than 1 means that the outbreak will eventually burn itself out. This happens less rapidly in the ‘surge’ scenario (decrease to R=0.9) than in the other scenarios (decrease to R=0.8).

Peak in ICU occupancy varies from 150 to 800 beds in the scenarios

The key outcomes of the scenarios are presented in Table 2. In the ‘smouldering fire’ scenario, maximum ICU occupancy due to COVID-19 has been estimated at 150 beds. A relatively minor increase in R has major consequences for maximum ICU occupancy. In the ‘peaks and valleys’ scenario, maximum ICU occupancy due to COVID-19 increases to 400 beds, despite measures implemented at 10 new IC (Intensive care) admissions per day. In the ‘surge’ scenario, maximum occupancy increases to 800 beds despite these measures.

ICU occupancy is important, but other indicators are also relevant

Besides ICU occupancy, other indicators are also relevant, such as the extent to which regular care is scaled down. If the capacity for COVID-19 patients exceeds 200 ICU beds, then regular care is scaled down in the ‘peaks and valleys’ scenario and the ‘surge’ scenario. The scaled-down situation will last 50 days or as long as 90 days, respectively. It is more difficult to determine the course of the total number of infected people. A high number of infections puts pressure on GP care and geriatric care, for example. This is also due to increased absence as a result of illness among health care workers. Some forms of care, such as care for the elderly and disabled, is more difficult to scale down.

Still many uncertainties in measures, treatment and a vaccine

The scenarios give an indication of how the course of events might progress. The outbreak may be lower if vulnerable groups are not affected, or as soon as an effective vaccine becomes available. Better treatment could also reduce the course of illness from COVID-19 and shorten the duration of admission. For example, if the duration of ICU admission drops from 19 to 10 days, the maximum occupancy of ICU beds in the ‘surge’ scenario decreases from 800 to 500 beds.

The outbreak may also be higher, for example if measures are not implemented until a later stage – or if efforts to bring the R below 1 are completely unsuccessful, if measures prove to be insufficient, or if compliance is poor. Scenarios in which the ICU capacity is not sufficient for the number of COVID-19 patients are not necessarily excluded here. Different scenarios could also occur in succession, or a sequence of small regional spikes could present a national pattern of a low, long wave.

Table 1: Situation and modelling assumptions for three scenarios for the course of spikes of the SARS-CoV-2 virus over a year, resulting in ICU admissions.

|

Scenario |

Background information |

Modelling assumptions |

|---|---|---|

|

Smouldering fire |

A small regional spike four times a year, but no clear wave pattern. |

Initial situation of 5 ICU admissions per day at R=1, average duration in ICU is 19 days. Each spike with two weeks at R=1.3, then R=0.8. |

|

Peaks and valleys |

A peak twice a year, which may be regional or national, in which the implementation of additional measures limits the extent of the spike. |

Initial situation of 5 ICU admissions per day at R=1, average duration in ICU is 19 days. Spike at R=1.5. Measures implemented at 10 ICU admissions per day1 + 3 days waiting for implementation, then R=0.8. |

|

Surge |

A large national wave that is difficult to control by implementing measures. Then a year of scenarios alternating between smouldering fire and peaks and valleys. |

Initial situation of 5 ICU admissions per day at R=1, average duration in ICU is 19 days. Spike at R=1.8. Measures implemented at 10 ICU admissions per day1 + 3 days waiting for implementation, then R=0.9. |

Want to read more?

The website presents more in-depth information on this topic (in Dutch).

Table 2 : Outcomes of the three scenarios for maximum ICU occupancy due to COVID-19 and possible consequences for regular care during highest peaks.

|

Scenario |

Scale |

Scaling up measures against SARS-CoV-21 |

Maximum ICU occupancy due to COVID-19 |

Creating ICU capacity for COVID-192 |

Duration of downscaled regular care3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Smouldering fire |

Regional |

No |

150 |

No |

0 days |

|

Peaks and valleys |

Regional / National |

Yes |

400 |

Yes |

50 days |

|

Surge |

National |

Yes |

800 |

Yes |

90 days |

1: Assuming that measures are implemented at 10 ICU admissions per day.

2: Assuming a free capacity of 200 ICU beds for COVID-19 care.

3: The period in which ICU occupancy rises above 200 ICU beds during the spike.

Figure1: Results of scenario analysis for the course of the number of ICU beds occupied for COVID-19 over two years. The brown part of the line indicates the first wave and is based on data, while the orange part of the line is based on a model with input data from Table 1.

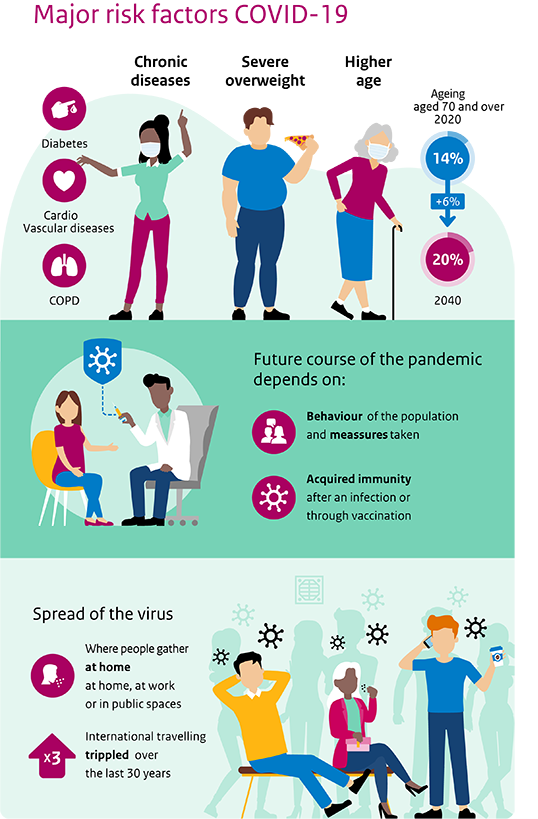

There is a possibility that SARS-CoV-2 or some other coronavirus will continue to cause outbreaks in the future, even if there is a vaccine against it. Risk factors for a serious course of illness from COVID-19 are advanced age, underlying diseases, and obesity. The Dutch population is ageing, and the number of people with chronic conditions is increasing as a result. Moreover, more and more people are overweight. As a result, the population becomes a little more vulnerable every year to developing a serious course of illness after infection with SARS-CoV-2, or a new virus that is comparable.

The coronavirus will probably linger, but the extent is uncertain

How the SARS-CoV-2 virus will spread in the long term is uncertain. There is a possibility that the SARS-CoV-2 virus may linger. The number of outbreaks, the scale of these outbreaks and the number of people who become seriously ill depend on various factors. These factors include the number of people who have built up immunity after previous infection or possible vaccination, and the duration of that immunity. The type of protection offered by such immunity also plays a role, and whether the immunity only protects the person from a serious course of illness, or also helps to prevent the spread of the virus. Finally, the behaviour of the general population and the government measures following outbreaks also play a role. The SARS-CoV-2 virus may also disappear if the immunity built up after an infection is long-lasting or if an effective vaccine becomes available.

Ageing population increases vulnerability to the virus

Several relevant factors increase the risk of a serious course of illness from COVID-19. These factors are elevated age, chronic health problems (e.g. diabetes, cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure and COPD) and obesity. 1.4 million more older people over the age of 70 will be added between 2020 and 2040 due to the ageing population. The ageing population also leads to an increase in the number of people with chronic diseases. More and more people are developing cardiovascular disease, diabetes and COPD. Obesity is also increasingly common among adults. As a result, the Dutch population will become slightly more vulnerable each year to a serious course of illness from COVID-19 in the coming decades. The impact on public health may increase as a result. This vulnerability also applies to infections involving other emergent viruses in the same risk groups.

Other developments may also be relevant

There are various developments that could influence the spread of a new pandemic. Most SARS-CoV-2 infections appear to take place within the home. Since the average household size is decreasing and the number of one-person households is increasing, the virus may not be able to spread as quickly in the future. On the other hand, continuing urbanisation and the associated increase in busy public spaces may make it possible for a virus to affect more people more quickly. Older people will continue to live at home independently for longer. As a result, the virus may not be able to spread as quickly in this vulnerable group as when elderly people live together in a nursing home. There are other developments as well, although it is still unclear to what extent they are related to a serious course of illness from COVID-19. Poor air quality may lead to increased risk of developing a serious course of illness from COVID-19, but further research is needed. Air quality is expected to continue improving in the future.

Possibility of new pandemics in the future

In the future, viruses similar to SARS-CoV-2 may cause new pandemics in the Netherlands. Due to a sharp increase in international travel in the last 30 years, viruses are able to reach the Dutch population faster and more often. Global urbanisation, population growth, increased food production and livestock farming, and changes in ecosystems are also factors that increase the risk of new pandemics. However, the population’s vulnerability to new viruses is determined by which age group is most vulnerable during a new pandemic with a new pathogen. The elderly have the highest risk of becoming seriously ill from COVID-19. In the 2009 influenza pandemic, older people were less susceptible.

Want to read more?

The website presents more in-depth information on this topic (in Dutch).

Health Inleiding

Health

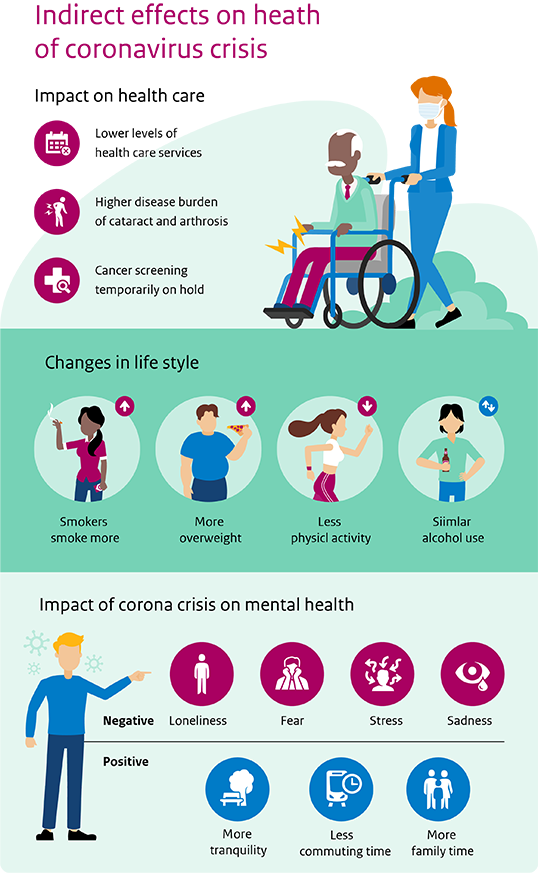

The pandemic and the measures adopted in response have an impact on various aspects of our health. Mortality from COVID-19 will probably be in the top 3 causes of death in 2020, and life expectancy will be lowered by six months. There is also a clear link between the COVID-19 pandemic and mental health, and our lifestyle has changed. If more people start smoking or become overweight as a result of the COVID crisis, for example, this will lead to increased mortality in the future. This study also looks at the health impacts as a result of the scaled-down availability of care, and the temporary discontinuation of population screening.

Health picture

Health infographic

Health tekst

More health loss

The COVID crisis has changed our lifestyle and behaviour; examples include smoking and overweight. This will lead to more health loss in the future, including increased mortality. In addition, postponing surgeries leads to an increased burden of disease. Due to the temporary discontinuation of population screening, fewer deaths due to cancer will be prevented.

Different impacts on mental health

The COVID crisis has a major impact on our mental health. The disease is feared, especially by older people, people who have a lower level of education, and people in poor health. In addition, the coronavirus measures have consequences. For example, we see that young people are especially stressed. Yet some people are also experiencing positive effects, such as more peace and quiet. The pressure on mental health could be intensified by the expected economic downturn.

Long-term effect of first wave on life expectancy is negligible

During the first four months of the COVID crisis, almost 10,000 more people died than in the same months of other years. COVID-19 has been established as the official cause of death for more than 6,000 of them. Excess mortality is at nearly 10,000, lowering life expectancy by six months in 2020 compared to earlier projections. These effects have a negligible impact on life expectancy in the future.

The health theme consists of the following articles

The COVID crisis has changed our lifestyle and behaviour. Smokers have started smoking more, and more people are overweight. This will lead to more health loss in the future, including increased mortality. In addition, postponing surgeries will increase the burden of disease. Due to the discontinuation of population screening during the first wave, fewer deaths due to cancer will be prevented.

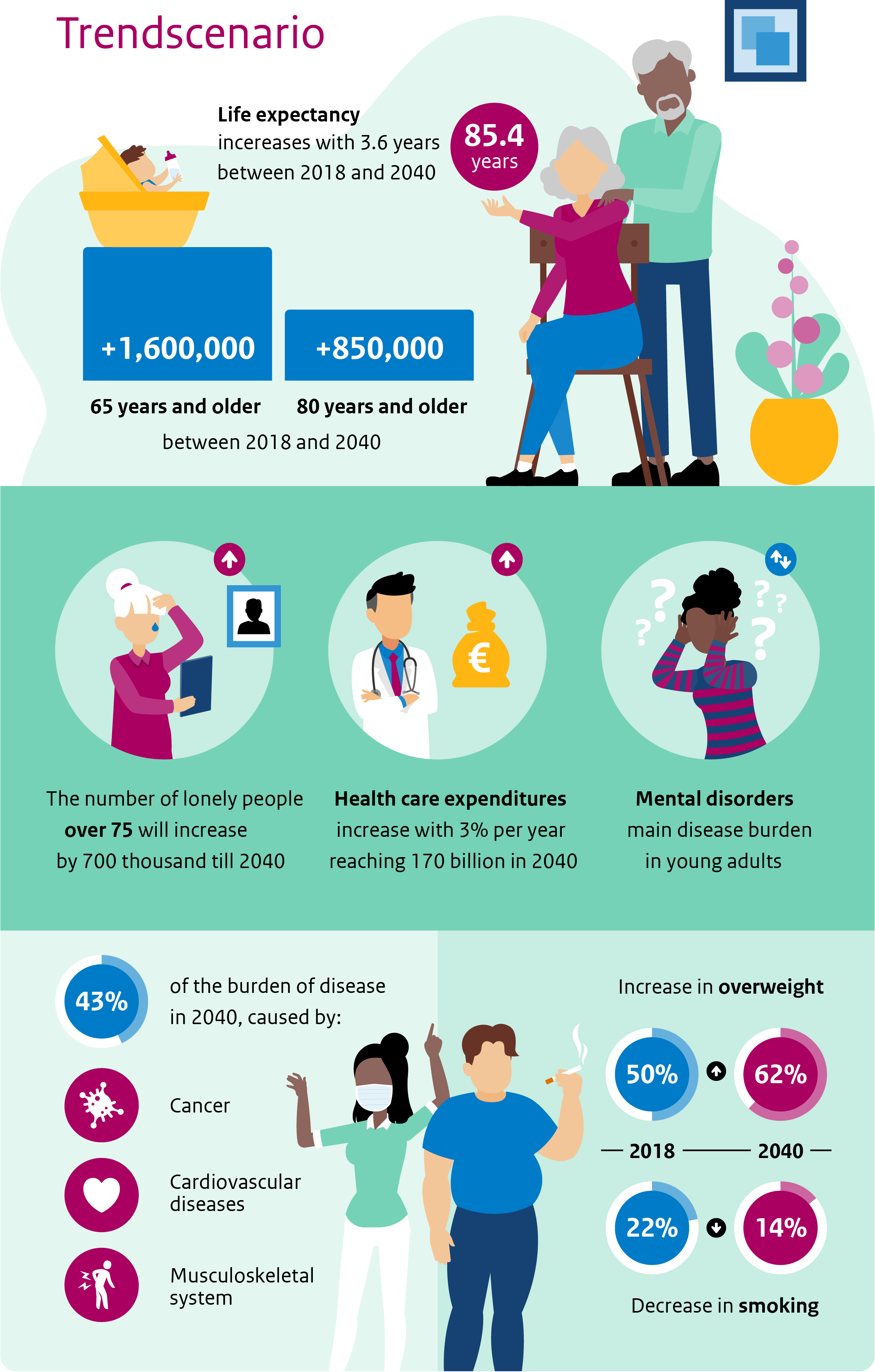

Cardiovascular disease and cancer remain major challenges

The persistently high burden of disease from cardiovascular disease and cancer was one of the major public health challenges in the Netherlands, before the COVID-19 pandemic. An unhealthy lifestyle, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, lack of exercise, overweight and an unhealthy diet, is a major cause of this burden of disease. Future projections from before the pandemic showed both healthy and unhealthy lifestyle developments. Smoking was anticipated to continue declining in the next few decades, while overweight was expected to increase. Trends were less clear-cut for alcohol consumption, as the third determinant of the National Prevention Agreement. The Trend Scenario presenting the future projections for the key trends has been updated for the c-PHFS. The Trend Scenario extends current trends forward into the future and does not incorporate the effects of the Prevention Agreement. The Trend Scenario is used as a frame of reference for comparing the consequences of the COVID crisis.

An unhealthier lifestyle due to COVID-19

The changes in lifestyle and behaviour may also cause deviations from these expected trends. During the COVID crisis, smokers started smoking more and we became more overweight. Surveys by RIVM (Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu) and GGD (Gemeentelijke/gewestelijke gezondheidsdienst) GHOR (Geneeskundige Hulpverleningsorganisatie in de Regio) Nederland showed that nearly 30% of people had put on weight, but also that about 16% had lost weight. Our behaviour in terms of movement and exercise has changed profoundly, for example due to the increase in working from home and to the measures that limit sports. Immediately after the measures were implemented, 53% of people indicated that they were exercising less, while 13% indicated that they were exercising more. Average alcohol consumption does not seem to have changed much as a result of the COVID crisis. Most of these trends seem to be headed in a direction that is less than beneficial for health, although knowledge is still limited.

Health loss mainly in the longer term

The Trend Scenario shows a steady decrease in smoking, from 22% in 2020 to 14% in 2040. This percentage may end up being higher due to the COVID crisis. Assuming that the percentage of smokers over the next 5 years is only 1 percentage point higher than in the Trend Scenario, the number of annual deaths due to smoking will already be about 200 higher in 2025-2035 (see Figure). If smoking behaviour remains structurally higher – which is certainly not inconceivable where addictive substances are concerned – the effect will be more significant. If the percentage of smokers is 1 percentage point higher than in the Trend Scenario over the entire period up to 2040, the number of deaths due to smoking will increase by an average of 700 per year.

The Trend Scenario shows an increase in overweight, from 50% in 2018 to 62% in 2040. If the COVID crisis causes an increase of 1 percentage point in the number of people who are overweight, this could lead to 60-100 additional deaths annually. A larger increase in overweight will also lead to an increase in health conditions such as diabetes, coronary heart disease and stroke. The effect on preventing these conditions has not been quantified. In terms of smoking, overweight and obesity, future trends are less favourable for the lower educated.

Health effects due to scaling down and avoiding regular care

The COVID crisis has put pressure on regular care. Regular care has been scaled down due to the high number of COVID-19 patients, and people are avoiding care for fear of becoming infected. As a result, surgeries are cancelled or postponed. This primarily affected less urgent care; acute care could generally be delivered as usual. However, delays in less acute care could also lead to significant potential health loss. As an example: in the first months of the COVID crisis, 25,000 cataract surgeries and 10,000 hip and knee replacement surgeries were not performed as planned. In terms of health loss, this means an increase of 2,000 DALYs for cataracts (15% increase) and 3,000 DALYs (2% increase) for knee and hip arthritis. This effect will intensify if care has to be scaled down again in subsequent waves.

Discontinuation of population screening during the first wave: fewer deaths avoided

Population screening for breast cancer, cervical cancer and bowel cancer makes it possible to detect these diseases at an earlier stage. Breast cancer and cervical cancer screening prevent 1,000 and 250 deaths each year respectively. Bowel cancer screening will prevent 2,500 deaths annually in the longer term. Population screening was put on hold for three months during the first wave, and then slowly started up again. An assumed delay of six months would lead to between 14 and 24 more deaths from breast cancer not prevented per year on average in the period between 2020 and 2039. There would be an average of 1 less death from cervical cancer prevented per year, and 13 to 103 fewer deaths from bowel cancer prevented per year. The results will be more favourable if the backlog is resolved by deploying additional capacity. The effects may become less favourable if population screening is limited again by subsequent waves of COVID-19.

Want to read more?

The website presents more in-depth information on this topic (in Dutch)

Graph: Mortality due to smoking

Sla de grafiek Mortality due to smoking over en ga naar de datatabelThe COVID crisis has a major impact on our mental health. The disease is feared, especially by older people, people who have a lower level of education, and people in poor health. In addition, the consequences of the measures have an impact. For example, we see that young people are especially stressed. Yet some people are also experiencing positive effects, such as more peace and quiet, less time spent travelling, more time with family, and a sense of connection to others. Knowledge about the health impact of other disasters and crises suggests that mental health will be less favourable, especially given the expected economic downturn accompanied by higher unemployment. Mental health can recover from the effects of the COVID crisis in the longer term, however.

Effect of COVID crisis on mental health differs per population group

There is a clear link between mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. Immediately after the COVID-19 outbreak, almost 40% of the Dutch population felt more anxious than before. One-third of the population felt more despondent, and one-third felt more stressed and anxious than before the crisis. Not everyone expresses these effects in the same way. COVID-19 is especially feared by older people, people who have a lower level of education, and people with underlying health problems, such as chronic respiratory or pulmonary problems, heart conditions and diabetes. Other groups in society suffer more from the consequences of the measures. For example, benefit recipients and disabled people mainly feel anxious, while young people mainly report feeling stressed. Another consequence of the crisis is loneliness. In April, more than a quarter of the population felt lonelier than before the crisis. This is especially notable among older people, young people, the lower educated and people on low incomes. The survey by RIVM (Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu) and GGD (Gemeentelijke/gewestelijke gezondheidsdienst) GHOR (Geneeskundige Hulpverleningsorganisatie in de Regio) Nederland shows that the percentage of people who felt somewhat lonely or very lonely has decreased since the end of April. It dropped from 71% at the end of April to 47% in July-August, after which there was a slight increase to 51% in September-October.

Negative, but also positive effects of the COVID crisis on mental health

Besides feeling more anxious, stressed and (very) despondent, people also experience positive effects. People experienced peace and quiet during the COVID crisis, spent less time travelling and more time with the family because they worked from home more, and felt more connected to others. Positive effects were also seen in very specific groups, such as people with autism. The coronavirus measures led to reduced overstimulation for some of these people, since life was less hectic and working from home reduced the difficulty they might have with all the social encounters that are often difficult for them.

Mental health after disasters varies over time

Little information is available about the mental consequences of long-term and large-scale disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic. ‘Flash disasters’ such as the Bijlmer plane crash or the Enschede fireworks disaster are experienced in different phases. In the ‘impact phase’, disbelief, astonishment and fear are the dominant emotions. This is followed by the ‘honeymoon phase’, featuring a noticeable sense of connection and solidarity. This could explain why the perceived health in certain periods during the first wave was higher than other years. This feeling was reinforced by the fact that the government came up with such responses as financial support packages.

The ‘disaster after the disaster’ reveals vulnerable population groups

The honeymoon phase is followed by the ‘disillusionment phase’, in which people become fatigued and exhausted. In the current crisis, for example, distancing and working from home are still in effect, while people want to return to their normal lives again. There is also a growing awareness that financial aid from the government cannot be unlimited and that the bill for those expenses will still have to be paid. In this phase, also known as the ‘disaster after the disaster’, the vulnerability of different population groups becomes more visible and tangible. The final phase is the recovery phase, in which people pick up their lives again. Knowledge gained from other disasters shows that emotional well-being can recover once that happens, but recovery may also take years.

Many socio-economic effects yet to come

The disaster after the disaster could become even worse when the socio-economic consequences, such as rising unemployment and income insecurity, become noticeable. The Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis (CPB (Centraal Planbureau)) now estimates that it will take 5 years for unemployment to return to its former level. New waves of the COVID-19 pandemic could still slow this down. Ongoing limiting measures will reduce the number of social contacts for specific groups, such as the elderly, and more people will feel lonely and isolated. This can in turn be accompanied by psychological problems, such as depression, which can lead to a vicious circle. A deterioration in mental health among certain groups of the population was also observed in previous crises. Taking this into consideration, the future prospects for mental health do not seem very positive for the upcoming years.

Want to read more?

The website presents more in-depth information on this topic (in Dutch).

During the first four months of the COVID crisis, from 1 March to 1 July 2020, almost 10,000 more people died than in the same months of other years. COVID-19 has been established as the official cause of death for more than 6,000 of them. However, the total mortality due to COVID-19 is higher than 6,000, because COVID-19 is not known to be the cause of death in relation to some of the mortality due to COVID-19. This usually concerns people who were not tested for COVID-19. The total mortality due to COVID-19 has also been increasing in the second wave. That would put COVID-19 in the top three of the main causes of death for 2020. Excess mortality is at nearly 10,000, lowering life expectancy by six months in 2020 compared to earlier projections. These effects have a negligible impact on life expectancy in the future. Life expectancy will also decrease temporarily if new waves of the pandemic cause additional mortality. There will be hardly any long-term decrease in life expectancy due to COVID-19. Life expectancy is projected to increase from 81.8 years in 2018 to almost 85.4 years in 2040.

COVID-19 in third place in list of causes of death for 2020

As a result of the deaths in the first and second waves in 2020, COVID-19 is likely to be ranked third on the list of causes of death, comparable to lung cancer (10,300 deaths) and stroke (8,400 deaths). Dementia remains the leading cause of death at approximately 17,900 deaths (see figure). These figures do not take into account the fact that mortality from dementia may be lower because COVID-19 is now registered as the cause of death in these cases.

Excess mortality has lowered life expectancy by six months in 2020

People who are in poorer health are more likely to die from COVID-19. As a result, the number of deaths in 2021 is anticipated to be slightly lower than expected. Many of the people who would have died in 2021 under normal circumstances have already died of COVID-19 in 2020. If that is the case, life expectancy in 2021 could be higher than in the most recent population forecast for a few months.

Increased life expectancy in the longer term, despite COVID-19

In the long term, the effect of the first and second waves on future life expectancy is negligible. The upward trend in life expectancy in recent decades is expected to continue in the longer term. This means that life expectancy at birth between 2018 and 2040 will increase from 81.8 years to 85.4 years. This means that we will gain nearly 4 more years of life over the next 20 years. Life expectancy may decrease temporarily during future epidemics that involve increased mortality.

Excess mortality and effects on life expectancy are averages

It is important to note here that mortality and the effects on life expectancy are averages for the entire Dutch population. The effects may work out differently for different population groups. For example, during the first six weeks of the pandemic, excess mortality was relatively higher in people who have a migrant background. There were no clear differences in excess mortality between people who were higher or lower educated or had higher or lower incomes. The health inequalities between different socio-economic groups were already significant before the COVID crisis: lower-educated men live 6 years less and lower-educated women live 4 years less than those who are higher educated. And in fact, higher-educated people live 14 years longer in good perceived health than lower-educated people (healthy life expectancy).

Want to read more?

The website presents more in-depth information on this topic (in Dutch).

Graph: Mortality by cause of death

Sla de grafiek Mortality by cause of death 2020 over en ga naar de datatabelHealth care picture

Health care Inleiding

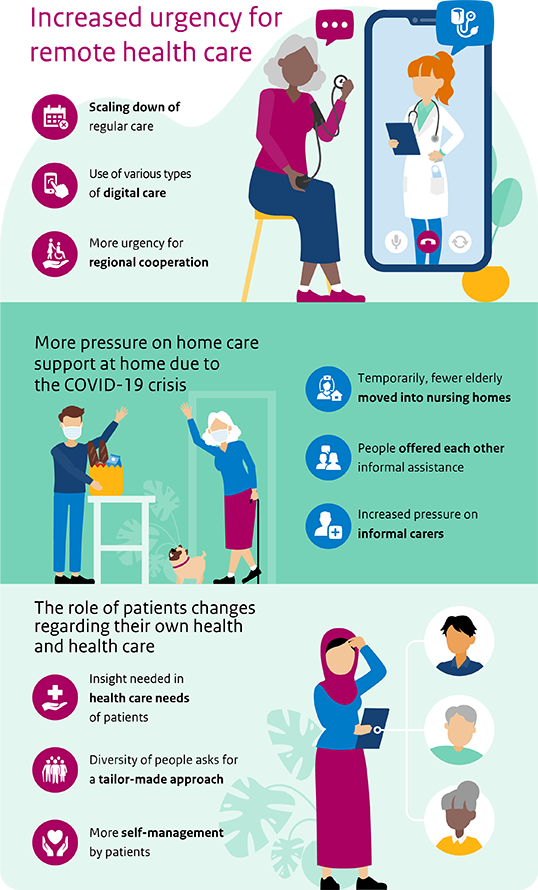

Health care

The demand for care is changing. Health care expenditures are increasing, and there is a growing shortage of care workers. How can we continue to meet people’s care needs? What trends do we see in the demand for care and support, how it is designed, and how resources like technology are used? The pandemic and associated measures have temporarily shut down part of our health care system within a short time frame. What are the short-term impacts of this, and is it already possible to say anything about the longer-term effects? This question will be addressed based on the following themes: the health care system, the provision of care (at home and in the neighbourhood) and the perspective of the patients and residents

Health care tekst

Digital care and regional cooperation are more urgent

The Dutch health care system is under pressure. Mitigating measures such as digital care and regional cooperation have been a strong focus for some time now. These developments have accelerated rapidly due to the pandemic. Digital media made it possible to provide remote care. Local and regional cooperation was intensified to provide the necessary care. Whether these changes will remain in effect in the future depends on various factors.

More pressure on care and support at home

Home care was already under pressure, and that pressure has been intensified by the pandemic. For example, fewer elderly people moved into nursing homes during the first wave, and pressure on informal carers intensified. This only adds to the pressure from the declining number of potential informal carers. The challenge is to provide good care and support at home, integrated where necessary, and to ensure that it is aligned to the client’s care needs, despite this increasing pressure.

More self-management requires commitment and support

The importance of self-management of health and health care had already been acknowledged before the COVID-19 outbreak. During the pandemic, the role of patients in relation to their own health changed. A clear overview is needed of the general and care-related needs, skills and health competences of residents and patients. This will make it possible to support their role in health and health care more effectively in future.

Health care Infographic

The care theme consists of the following articles

The Dutch health care system is under pressure. The ageing population is accompanied by a growing and increasingly complex demand for care. The increasing shortage of care workers on the labour market makes it more difficult to meet that demand. For that reason, mitigating measures such as digital care and regional cooperation have been a strong focus for some time now. These developments have accelerated rapidly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Digital media made it possible to provide remote care. Local and regional cooperation was intensified to provide the necessary care during the pandemic. Whether these changes will remain in place depends, among other things, on the sense of urgency to work together with local, regional and national partners. The effectiveness, accessibility and feasibility of digital care also need to be researched.

Increasing pressure on health care system requires a different approach

Even as pressure on the health care system is increasing, a different approach to care is emerging. There is a shift from illness and care to health and behaviour, incorporating a broader definition of health. This requires a different way of working in the health care system. More and more attention is being paid to integrated care and cooperation between different domains. The care needs of residents and patients are more central in this context. This transition takes time. Acceleration seems to require a stronger sense of urgency, and certain factors must be arranged. That includes a solid digital structure for knowledge and information, alternative forms of funding, and an active role for clients and patients in shaping their care and support.

First wave of COVID-19 had a major impact on care and support

During the peak of the first wave of COVID-19 in the Netherlands, regular and plannable care was postponed, scaled down or replaced. Regular care largely restarted again in summer 2020, when infections were low. Hospitals announced in autumn that they would have to scale down part of their care again. To continue providing care and support (in person or remotely) during the first wave, the use of digital alternatives in care and support increased. They were primarily used for consultations. Experiences with digital care vary by care sector and target group, and more extensive evaluations are required for a balanced assessment. A better understanding of effectiveness and future-proof funding are needed to ensure an increase in the use of digital care.

Increasing urgency to cooperate in the region

Regional cooperation has become more urgent due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The results vary in actual practice. Several regions cooperated more effectively. However, there are also examples in which certain organisations were not taken into consideration in cooperation related to COVID-19. Whether regional cooperation is retained in the future depends – aside from an ongoing urgency – on multiple factors. Examples include funding options, a shared societal purpose, and a clear point of contact as well as a clear division of responsibilities.

Strong focus on cure, less so on broader health perspective

During the first wave of COVID-19, the emphasis was on providing urgent care and COVID-related admissions to hospital and ICU. As a result, there was less of a focus on the broader health perspective that had been emerging. It became apparent that there is less room for broader views and extensive consideration in crisis conditions. This holds true for health as well as prosperity. However, it is important to return to that broader approach – so the other aspects of health, such as quality of life, participation and a sense of meaning and purpose, can have a place when policy measures are being considered during a new wave of COVID-19, or a new pandemic.

Regular care, scaling down or up: prioritising care according to usefulness?

When the pressure of COVID-19 on the health care system began ebbing away after the first way, it became possible to scale up regular care step by step. To ensure that the capacity was deployed in such a way as to maximise health benefits, the Minister for Health, Welfare and Sport (VWS (Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport)) called for an approach that started by scaling up the most appropriate care. This requires insight into which care is more appropriate. Experience gained in scaling up and restarting care during the first wave of COVID-19 may offer more insight here. For this purpose, it is necessary to evaluate the effect of the care that was provided differently or in diminished amounts.

Want to read more?

The website presents more in-depth information on this topic (in Dutch).

Home care was already under pressure, and that pressure is continuing to grow due to the pandemic. For example, fewer elderly people moved into nursing homes during the first wave. Pressure on informal carers has also increased, because facilities offering adult day services closed and care was scaled down. This only adds to the pressure from the declining number of potential informal carers. The challenge is to provide good care and support at home, and integrated where necessary, and to ensure that it is aligned to the client’s care needs, despite this increasing pressure.

Even before COVID-19, increasing pressure on home care was expected

The demand for care and support at home was already expected to increase, even before the COVID-19 outbreak, due to the ageing population and the developments in the field of health care. More people need care, and the demand for care is becoming increasingly complex. Multimorbidity (having multiple health conditions at the same time) and psychosocial aspects play an increasingly major role in this context. Moreover, there is a growing shortage of care and welfare workers, and the number of potential informal carers is expected to decline.

Impact on the use of care in the neighbourhood and at home

The COVID crisis has an impact on the influx and outflux of care and support in the neighbourhood. For example, during the first few months of the COVID crisis, elderly people opted not to move into a nursing home, or to postpone that step, according to a study by the Dutch Healthcare Authority (NZa) on neighbourhood care. Clients also received less care at home, either by their own choice or due to scaled-down care.

Loneliness and isolation due to scaled-down care and support

The scaled-down care and support during the first wave of COVID-19 led to feelings of loneliness and isolation. That was the case for older people as well as teenagers, people with a mild or severe intellectual disability, people with a complex care demand, and people in vulnerable health. It was also the case for vulnerable families. These people benefit most from formal and informal care and support at home and in the neighbourhood. During the first wave of COVID-19, this care and support was jeopardised.

Increased pressure on health care professionals and informal carers

Due to the scaled-down care and support, informal carers perceived a greater sense of pressure. For example, in a poll posted by Mantelzorg NL, an informal carers’ organisation, nearly 60% of informal carers responded that they had provided more care. In addition, the concerns about the health of their loved ones can put extra pressure on the informal carers. These concerns may play a role both during a COVID-19 peak and when measures are eased. To eliminate uncertainty wherever possible, it is important to provide clear information about the risk of infection and the options for digital contact.

Want to read more?

Op The website presents more in-depth information on this topic (in Dutch).

The importance of self-management of health and health care had already been acknowledged before the COVID-19 outbreak. During the pandemic, the role of patients in relation to their own health changed. On the one hand, the emphasis on personal responsibility for health and healthy behaviour increased. On the other hand, there was less room to respond to people’s need for care and support, because the health care system was under greater pressure. A clear overview is needed of the general and care-related needs, skills and health competences of residents and patients. This will make it possible to support their role in health and health care more effectively in future.

Different role for patients and residents was already evolving before the crisis

The role of patients was already changing in response to the various changes in the health care system. Patients are increasingly expected to take responsibility for their own personal health. There is a stronger emphasis on self-management and patient-focused care. This requires the patient to take on an active role in his own care process. In addition, efforts are being made to give people more control over the design of their health and care, for example a say in what care should look like in their neighbourhood or community. At the same time, people are dealing with a fragmented health care system that they perceive as inaccessible. Also, not everyone has the health skills needed for self-management. Not everyone is able to take responsibility for health, health care and health insurance. This intensifies existing health backlogs.

Caring for each other more during the crisis

During the first wave, people offered each other more informal assistance. Due to the increased pressure on the care system, care and support were scaled down, and fewer resources and formal help were available. As a result, people, including informal carers, felt more pressure to offer this support themselves. People are expected to continue playing a greater role in providing informal assistance even after the crisis. Informal help remains necessary to fulfil the demand for care. Among other things, resident initiatives and informal carers need financial and organisational support to sustain this in the long term.

Recentring health care needs

During the first wave of COVID-19, residents and patients were minimally involved in the development of coronavirus measures, policies and suitable options for care. In order to ensure that the health care system is sufficiently aligned with the care and support needs, it is important to involve children, young people, older people, adults and vulnerable groups in this development. In doing so, we have to take into account the different support needs of different groups of people. For example, during the first wave of COVID-19, pre-existing health inequalities seem to have increased. The importance of gaining insight into the general needs and care needs of people with health and other disadvantages and limited health skills is thus increased

Want to read more?

The website presents more in-depth information on this topic (in Dutch).

Living environment Inleiding

Living environment

During the COVID crisis, we quickly saw the first (temporary) changes in the living environment. The air was cleaner and noise levels from traffic went down. The immediate surroundings, nature and public spaces, became more important to residents. The environment in which people live, work, learn and play has a major influence on their behaviour and their health. The design of the living environment can be improved in various respects. The COVID crisis has showcased this, while offering opportunities. By finding smart ways to link climate policy with health policy, spatial planning and the COVID-19 crisis recovery policy, we can achieve health and prosperity gains while taking vulnerable groups in society into account.

Living environment foto

Living environment Infographic

Living environment Tekst

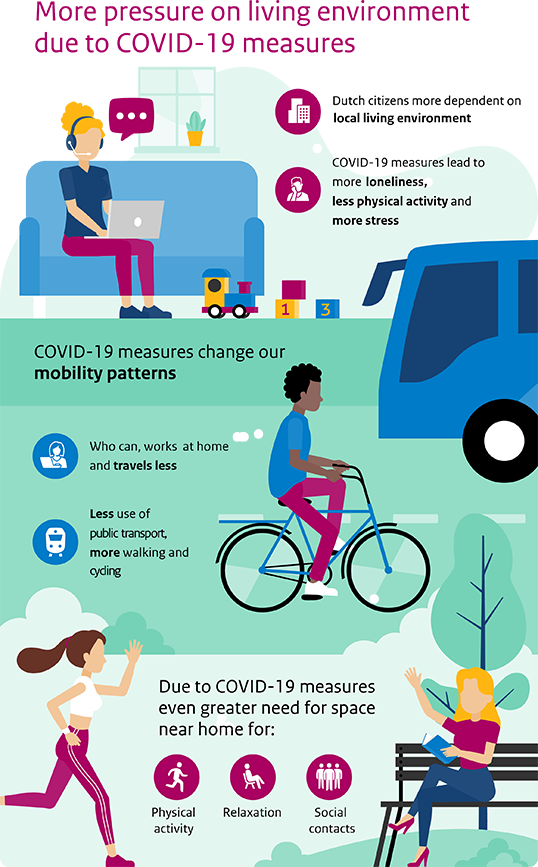

More pressure on public spaces

There is huge demand for new homes, especially in cities. It is a challenge to combine urban compaction with enough room to move and exercise, relax and meet up with others. The coronavirus measures led to increasing pressure on public spaces. The measures also have consequences for social connections in the neighbourhoods. The challenge for the future is to structure the living environment in such a way that it is safe and healthy for everyone, especially vulnerable groups.

Moving and exercising differently due to coronavirus measures

Because of the coronavirus measures, we use public transport less intensively and we cycle and walk more often. More than half of the people currently working from home would like to work from home more often in the future, and many cities are making neighbourhoods car-free in favour of cyclists and pedestrians. This development reinforces municipal policies to provide incentives for sustainable mobility. This has a positive impact on exercise and environment-related health.

Impact of climate change on health

Climate change continues to move forward, despite the temporary drop in greenhouse gas emissions due to the coronavirus measures and economic trends. The consequences of this, such as extreme heat, drought or flooding, have a major impact on our health, society and economy. The consequences will be felt more and more. The COVID-19 recovery policy must include a focus on climate and its relationship to health.

The living environment theme consists of the following articles

There is huge demand for new homes, especially in urban areas. This means a further compaction of cities. It is a challenge to combine urban compaction with enough room to move and exercise, relax and meet up with others. The coronavirus measures led to an increase in pressure on public spaces. The measures also have consequences for social connections in the neighbourhoods. The challenge for the future is to structure the living environment in such a way that it is safe and healthy for everyone, especially vulnerable groups.

Major need for new homes

The Netherlands is facing a major construction challenge. According to the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL (Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving)), 95,000 new homes should be built each year until 2030 in order to solve the housing shortage. A further increase in the number of households is expected thereafter. To a considerable extent, these homes will be built within existing neighbourhoods. This may be done by building new homes, or e.g. by converting offices into homes. These extra homes put more pressure on public spaces, at the risk of leaving less room to move, get exercise, relax and meet up with others.

Green spaces, water and quiet(er) places have health benefits

The presence of greenery, water and (relatively) quiet places close to home contributes to good physical and mental health. This offers opportunities to relax, meet up with others, move around and get some exercise, and ensures water storage and less heat stress. In the years to come, people will increasingly use public spaces and green spaces for sports and exercise, such as cycling, walking or doing sports in parks.

Coronavirus measures increase pressure on public spaces

It is possible that a subsequent wave of COVID-19 in which measures are necessary could intensify pressure on public spaces even more. As a result of the coronavirus measures, groups of people, such as those working from home, make more frequent use of the public space in their neighbourhood. Closing down restaurants and stopping team sports for adults also brings people outdoors more often, which increases the pressure on the public space. It can become difficult in some locations to maintain a distance of 1.5 meters. This can lead, for example, to vulnerable elderly people no longer daring to go outside and becoming lonely more quickly. The limitation of opportunities for meeting in public spaces can also increase loneliness among teenagers.

Measures can be felt in your own district and neighbourhood

The measures have a stronger impact on groups that had strong ties to their own neighbourhood even before the coronavirus measures. That could include children, older people and people in a lower socio-economic position. For now, the increased pressure on the public space makes it difficult for them to find their own spots to play or relax in their own neighbourhoods. In addition, environmental problems often accumulate for people in a lower socio-economic position: from poor housing with moisture problems and mould, unhealthy indoor and outdoor air, to minimal greenery in the surrounding area leading to heat islands. The social quality of the living environment is also under pressure as a result of the coronavirus measures. Encounters between neighbours, which are important to feeling at home in the neighbourhood, become less casually automatic. The distancing measures also form a barrier for (vulnerable) residents to express their opinions and preferences about their living environment, for example in (online) consultation processes. However, residents’ initiatives and mutual assistance are emerging, taking a joint approach to overcome the COVID crisis. Greater involvement in the neighbourhood can reinforce social cohesion

Opportunities for a healthy living environment

Combining urban compaction with a healthy living environment will be a challenge in the future. Smart designs for a car-free, greener neighbourhood, for example, offer opportunities to link health and safety to other challenges, such as climate adaptation and mobility. In that context, it is also important to take the preferences of (vulnerable) residents into account from the start. In addition, digital media can offer insight into what is available in the surrounding area and how it is used. For example, if you are looking for places to go walking, it could include real-time updates on how busy it is in green spaces.

Want to read more?

The website presents more in-depth information on this topic (in Dutch).

Climate change continues to move forward, despite the temporary drop in greenhouse gas emissions due to the coronavirus measures and economic trends. The consequences of climate change, such as extreme heat, drought or flooding, have a major impact on public health, society and the economy. The consequences will be felt more and more over the course of the century. The COVID-19 recovery policy must include a focus on climate and its relationship to health.

Temporary drop in CO2 emissions, renewed increase expected eventually

The COVID crisis has led to a sharp drop in greenhouse gas emissions in the Netherlands and abroad. In the Netherlands, for example, CO2 emissions from the transport sector in the second quarter of 2020 were about half those of the previous year. However, emissions are expected to increase again after the crisis is over, once mobility possibly returns to the same level and the industrial sector is up and running again.

More heat-related mortality in future, less cold-related

The Netherlands has set weather records in recent years. Densely populated and intensively used, the Netherlands is vulnerable to climate change and its consequences, such as extreme heat, flooding, drought and reduced availability of water. These consequences have health impacts. This is already visible in higher mortality rates due to heat. An increase in allergies can also be expected. The elderly and people with chronic diseases experience the most impact from extreme heat and are more likely to die as a result. According to RIVM (Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu) calculations, 1,350 people died prematurely due to heat in 2020. In 2050, heat mortality will double. This mortality can be attributed in part to the ageing population. Later this century, around 2060, if the policy remains unchanged, there will be a significant increase in premature deaths due to heat. In the event of a sharp rise in temperature and without climate policies, this mortality will be far higher than mortality due to cold periods. This is because the chances of extreme cold are decreasing.

Climate change, ageing and compaction reinforce each other

A number of trends will converge in the following years that can potentially reinforce each other. For example, the ageing population means that more people will be vulnerable to climate change. Older people living independently are at additional risk, as are the elderly living in inadequately cooled nursing homes, which may cause care to fall short of acceptable standards during heat waves. In addition, compaction of the built environment in cities can create more ‘heat islands’.

Important to cool and ventilate buildings

Due to the expected increase in temperature, it will become increasingly important to arrange cooling and ventilation of homes, but also care institutions, schools, offices and factories. It must be possible to provide sufficient ventilation during the winter months, in part in relation to the risk of viral infections. Ventilation also plays a role in the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which may add a supplementary requirement to the current ventilation requirements in the Buildings Decree.

Integrated deployment of climate policy

The consequences of climate change are already visible and will be felt more and more in the coming decades. That is why it will be even more important to provide a place for greenery and nature in spatial plans. To address the causes of climate change, sectors that contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions need to become more sustainable, such as transport (air and road traffic), agriculture, health care, and energy. Successful climate policy that also improves air quality can lead to a 90-95% reduction in the burden of disease caused by air pollution. By finding smart ways to link climate policy with health policy, spatial planning and the COVID-19 crisis recovery policy, we can achieve health and prosperity gains. However, it is important to ensure that climate policy takes vulnerable groups in society into account. These groups often already have limited resources to invest in sustainability, such as insulation their homes, or purchasing energy-efficient appliances.

Want to read more?

The website presents more in-depth information on this topic (in Dutch).

Perspectives picture

Perspectives Inleiding

Perspectives on health for all ages

In the initial phase of the COVID crisis, there was understandably a strong focus on the health of COVID-19 patients and the care that they needed. The economic consequences of the measures also received extensive attention shortly after. There was less focus on some population groups who were no longer able to achieve optimal participation in society as a result of the measures. Perceived health, loneliness, self-management (control over one’s own life), quality of life, and a sense of significance also received comparatively less attention. With a view to the future, it is important to take these aspects of health into account in new policies as well.

Include multiple perspectives on health in future coronavirus measures

Health is more than COVID-19; everyone agrees on that. But opinions differ on exactly what that ‘more’ represents. Four perspectives on public health, developed for the PHFS-2014, provide an explicit look at this diversity of views. The perspectives focus on keeping people healthy as long as possible, supporting social participation for vulnerable people, promoting autonomy of citizens and patients, and keeping health care affordable. Taking all perspectives into account helps in shaping new, balanced policy measures. They also clarify the consequences of the COVID crisis for young people and for the elderly.

Four perspectives on public health

The four perspectives on health were developed on the basis of discussion meetings with over 100 stakeholders. Different goals and solutions are central in each perspective (see table). Dutch people do not all have the same vision of what a desirable future looks like in terms of public health. The perspectives can help us not to forget that diversity.

Two perspectives front and centre during the COVID crisis